Free

Foundation

Terms of Use

March 9 → July 9, 2023

Terms of Use brings together works that explore the impact of technologies on the definition, construction, and (re)framing of individual and collective selves

The Looks (2015) is a two-channel video installation by the artist Wu Tsang. It is a segment of the project, A day in the life of bliss. In these films, we follow the young performer Bliss (played by Tosh Basco), a pop star by day and an underground artist by night, who lives in a world where an artificial intelligence (AI) called “The Looks” controls human thought. This AI, imagined by Tsang, is inspired by our current algorithm-based metadata systems. It tracks all exchanges between people and makes society dependent upon it. “The Looks” cultivates this celebrity-obsessed culture, through which Bliss is slowly drifting. Fortunately, she is one of the minority of humans born with two hearts, which gives her the innate capacity to undermine the AI’s regime; but, to fully realize her potential, she must first accept herself.

This conversation between us, Belen Blizzard and Inès Allard, offers our perspectives and reactions after seeing The Looks. In this text, we discuss how performance is used as a channel for storytelling and emotion; the way this sci-fi movie is resonating with our present; and the different dualities that we find in this fragment of Bliss’s story.

Belen: I was really struck by the dichotomy of being seen and unseen that’s predominant in the film. As Bliss sings about being “untouchable,” her appearance starts to glitch; the myth of being able to distance oneself from others is revealed to be dysfunctional. Through her performance, Bliss is made to be hypervisible, which cannot be separated from being “touched.” I was also captivated by her costume: the glitter covering her entire body seemed to act as both an armor and a cage. Her costume seemed to illustrate an interplay between protection and vulnerability. By transforming her appearance, she can access a sense of detachment from the reality of being a human. However, this detachment is temporary and fleeting; being visible is a constant reminder of that.

Inès: For me, the first thing that came to mind was boychild’s (the performance name of Tosh Basco) performance and the way that Wu Tsang was able to capture it through her cinematography. I focused first on the feeling that the film was conveying. It’s interesting to see how they translated the experience of a live performance, which is usually experienced IRL, to film. I was absorbed by the narrative and the movement, as if I was in the same room as Bliss. In a way, I do feel like I was kind of participating in The Looks itself, being fully engaged with the life of Bliss, this character whose appearance and movement really fascinated me. I wanted to know more. Wu Tsang uses dreamlike cinematography, mostly in the first part of the film, which makes me, as a viewer, feel like Bliss is not a part of reality, but that she is instead floating in a fantasy.

I think that it’s interesting how, through science fiction, Tsang portrays our contemporary moment in a way that is accurate and relevant but also touches fantasy. By that, I mean the way Tsang uses a cinematography that is dream-like in certain parts, and you can almost feel how Bliss and even the other characters are drifting unconsciously through this metaverse, technological realm. Like us right now (laughs)! I believe that we are highly controlled by technology, or that we use technologies to control each other. Everything moves really quickly in our modern times. We are constantly ingesting information from the world in a way that is, most of the time, overwhelming. But I also think that we still have agency, and we are collectively making that decision to; keep up, adapt, or even fit in. It’s hard to calm the mind when things are moving quickly around you. I feel like Bliss is kind of experiencing something similar, and she’s not fully in control of her experience. The voice-over, who I imagine is either “The Looks” AI itself, or maybe Bliss’s inner thoughts, is making her question her choices and sense of reality.

Belen: Totally. It does feel like the world that’s portrayed is very similar to ours. It’s enhanced and seems futuristic, but as you’ve pointed out, it shares so much with our current reality. The hold that technology has on our lives is terrifying; it structures our relationships, our communication, our scheduling, our work opportunities, and deeper still, our perceptions of the world, our attention spans, our internalized beliefs. In response to what you were saying about the dreamy aesthetic, it feels like it’s echoing the feeling we have when we engage online, especially through social media; there’s a dissociative quality to it that’s portrayed in the film when the protagonist’s eyes turn white. As for us, it remains hard to name, or fully understand, but we know how deeply affected we are by our dependency on technology. In this sense, the film offers us an opportunity to be more critical of our current relationship with technology. Bliss’s performance gave me a weird, almost uncomfortable feeling…

Inès: Yes, definitely.

Belen: Yeah, this weird feeling, where I was like “oh, she doesn’t seem comfortable,” therefore I feel uncomfortable. There was something about the crowd as well, and being in the same position of viewership, that almost felt extractive. We could think of it as an analogy for technology; as you said before, there is a lot of control in our use of technology, and these platforms benefit immensely from our dependency on them, which is inherently extractive, and which is also fundamentally how capitalism functions (laughs).

Belen: I feel like there are many dualities portrayed in the film: from Bliss’s gender expression, which exists in a space of ambiguity, to her costume and performance, which seem to bridge the space between human and non-human… There is also the song, since she sings about the duality of the desire to be “untouchable” and the immediate failure of that, which stems from being a person in the world, which is to say, we can’t escape being touched by others. This desire to flee the inevitability of touch was partially what made me uncomfortable; touch is destructive and transformative and terrifying and beautiful, and that’s kind of what’s really special about being a human, is the inescapability of fracture through contact.

Inès: This is so interesting because I recently read that Tsang connected with boychild’s performance practice because she is able to transfer human emotions and feelings by embodying them. [1]

Belen: Exactly! Basco’s ability to convey so much affect and knowledge through her movements is beyond impressive. In her performance of Bliss, specifically when the character is on stage, the friction between “untouchability” and the impossibility of that, was felt in the motion of their body. Their performance was full of fractures; reading their facial expression, you can see them oscillate from super-star fluid delivery to a kind of suffering, or pleading. As they sing “contact, contact,” it kind of feels like a cry for help, like a human turned cyborg that actually remains human, begging for something else, something different, a life that is not drowned by hyper-visibility and continuous surveillance.

Inès: Precisely! What you just expressed feels like more than duality. Tsang has been exploring what she calls the “in-betweenness,” in her work. That is, “a state in which people and ideas cannot be described in binary terms.” [2] It’s exactly what we are seeing. The body, the mind, and the fantasy all collapse, conjunct, transform, and transcend into each other.

Belen: Yes! Also, knowing that both Tsang and Basco work closely with the theorist Fred Moten, I can’t help but think about a word that he coined with his collaborator Stefano Harney: “hapticality.” In their own words, hapticality is “the capacity to feel through others, for others to feel through you, for you to feel them feeling you.” [3] This feeling is what ties us to one another; it blurs boundaries and really illuminates, as you said, the body/mind/fantasy’s capacity to go beyond any kind of duality. Bliss’s plea to be untouchable is made impossible through their haptic disposition; it kind of feels like, through feeling the audience, the screens being pointed at them, the lights, the surveillance, Bliss collapses on stage due to this exchange of feeling, the porousness of being in the world, and the inevitability of being touched.

Inès: Yes, beautifully put! There’s one last thing I have to say about Basco’s performance that really caught my attention. In the first part of the film, there is a scene where Bliss is covered in white powder as she bends and contorts her body in ways that make me think of Butoh dance performances. [4] Butoh is a dance-theatre art form that was created by two Japanese choreographers (Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno) after World War II. The dance practice itself is hard to define, which is also part of the beauty of it, because it is open to a myriad of interpretations. From my perspective, because of the way Butoh dancers are contorting their bodies and faces, it feels like an analogy for suffering, distress, or even the transition to death, which brings into consideration the in-betweenness of spirituality—how life and death are always in dialogue and in relation. Bliss is oscillating in a multitude of different realms.

Belen: Yes, and her performance is so indicative of that oscillation; as she glitches, she disintegrates, and the film ends. That rupture leaves the viewer in the space of the unknown. Also, her movements kind of signify that interplay between life and death: from the suffering to the delivery, from the human to the glittery, Bliss seems to constantly be on the precipice of breaking down or of vanishing into the digital abyss, into a heightened commodification that leaves no space for their humanity.

I think The Looks really highlights the importance of movement for me. As a person that’s really drawn to language, it is fascinating to feel and understand so much from a film that is partially structured by language, but mostly centered on movement. I was touched by the beauty of translation: Tsang’s ability to capture performance and offer the viewer an experience that is so palpable and tangible, is truly incredible. Also, I guess it kind of fed the flames of fear with regards to surveillance and, upon reflection, heightened my own sense of discomfort with technology. I’m trying to shift my relationship with it, because it’s irreversible and I think there’s a lot of generative possibilities tied to technological growth; this excerpt of Bliss’s narrative didn’t necessarily point that out for me, however the film is a testament to those possibilities.

Inès: I was touched by the way Tsang and Basco were able to combine their artistic practices to transfer emotions through a sci-fi tinged realm. The Looks led me to understand how storytelling can take many forms, and how it is truly generative. There is a lot of power in being able to create an imaginary world that helps us process our current reality. I felt highly inspired by the power embodied by Basco in her performance and Tsang’s transformative figments of imagination.

[1] Holly Connolly, “Wu Tsang on communicating underground spaces in the age of social media,” The Vinyl Factory, November 27, 2018, https://thevinylfactory.com/features/wu-tsang-the-looks-interview/.

[2] Alex Greenberger, “Take Me Apart: Wu Tsang’s Art Questions Everything We Think We Know About Identity,” ARTnews, March 26, 2019, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/wu-tsang-12224/.

[3] Stefano Harney, Fred Moten, “Fantasy in the Hold”, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Brooklyn: Autonomedia/Minor Compositions, 2013.

[4] James Kim. “Butoh, Explained,” University of Michigan, 2019, https://ums.org/2019/10/17/butoh-explained/.

This article was written as part of Platform. Platform is an initiative created and driven jointly by the PHI Foundation’s education, curatorial and Visitor Experience teams. Through varied research, creation and mediation activities in which they are invited to explore their own voices and interests, Platform fosters exchanges while acknowledging the Visitor Experience team members’ expertise.

Authors

Belen Blizzard

Belen Blizzard (they/them) is an artist and student at Concordia University in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

Inès Allard

Inès Allard (they/them) is an artist and a Visitor Experience Coordinator at the PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art.

Free

Foundation

Terms of Use brings together works that explore the impact of technologies on the definition, construction, and (re)framing of individual and collective selves

Free

Foundation

Terms of Use brings together works that explore the impact of technologies on the definition, construction, and (re)framing of individual and collective selves

Foundation

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

Foundation

Six artists present works that in some way critically re-stage films, media spectacles, popular culture and, in one case, private moments of daily life

Foundation

This poetic and often touching project speaks to us all about our relation to the loved one

Foundation

DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art is pleased to present the North American premiere of Christian Marclay’s Replay, a major exhibition gathering works in video by the internationally acclaimed artist

Foundation

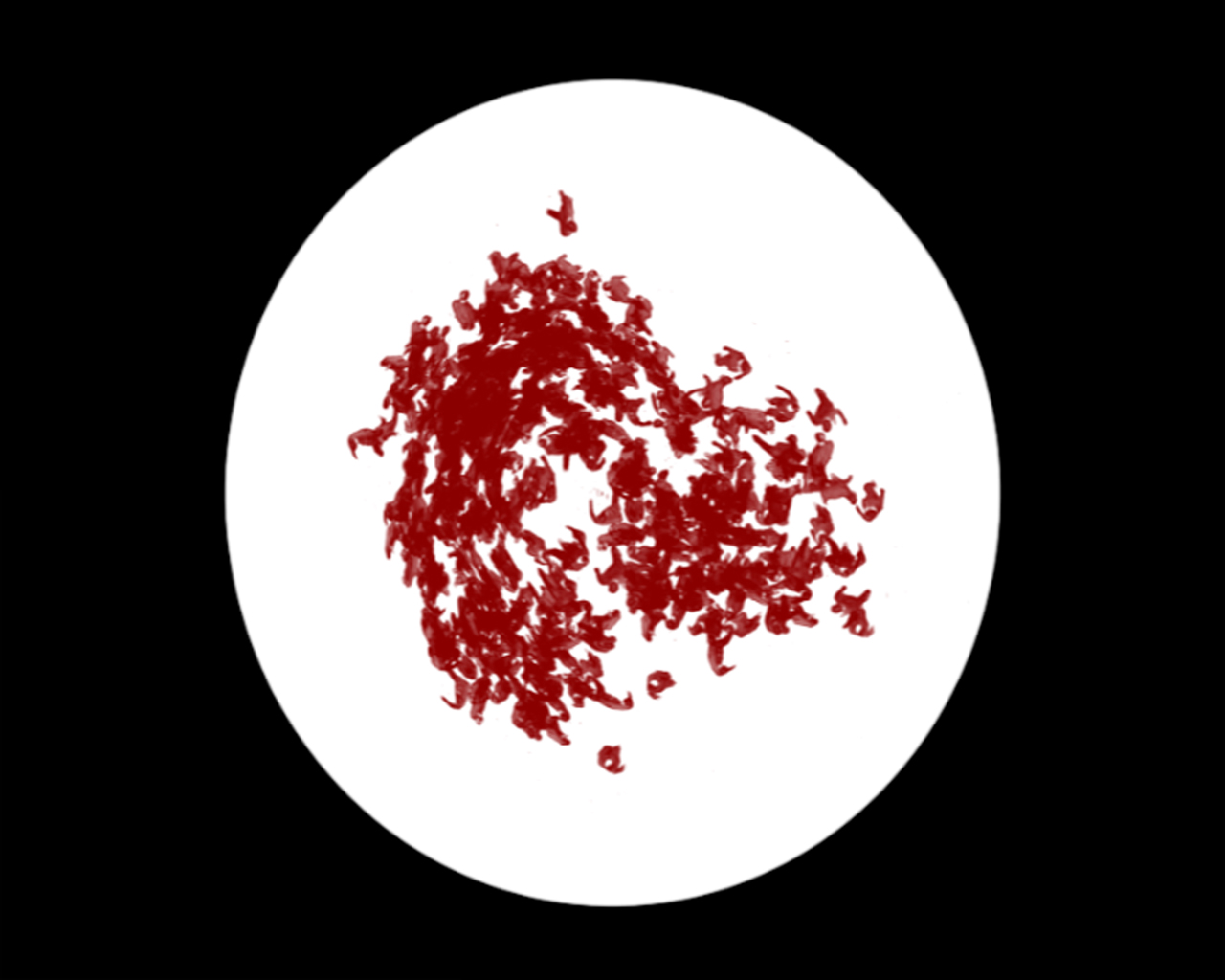

DHC/ART is pleased to present Particles of Reality, the first solo exhibition in Canada of the celebrated Israeli artist Michal Rovner, who divides her time between New York City and a farm in Israel

Foundation

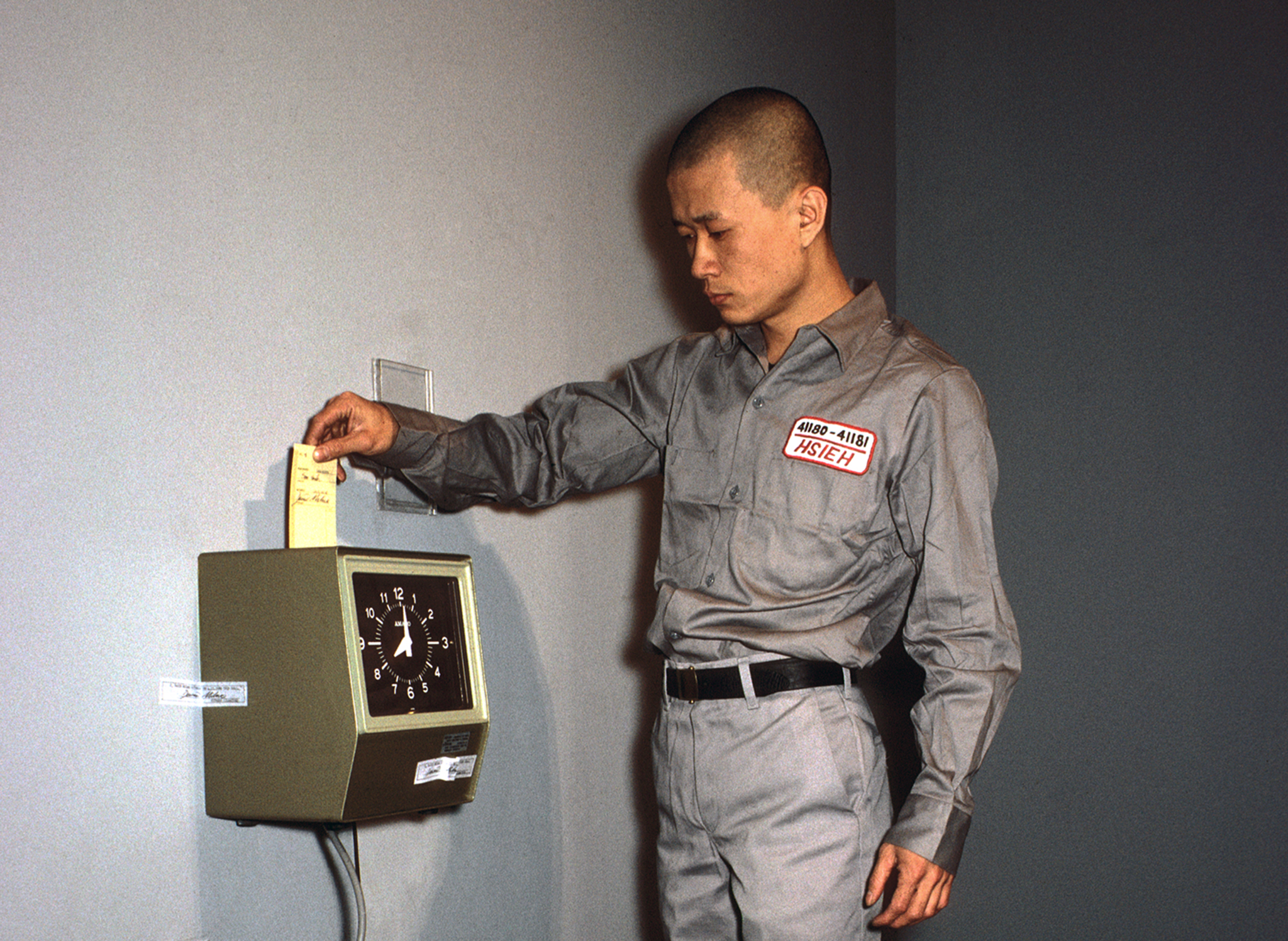

The inaugural DHC Session exhibition, Living Time, brings together selected documentation of renowned Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances and the films of young Dutch artist, Guido van der Werve

Foundation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film installations experiment with narrative storytelling, creating extraordinary tales out of ordinary human experiences

Foundation

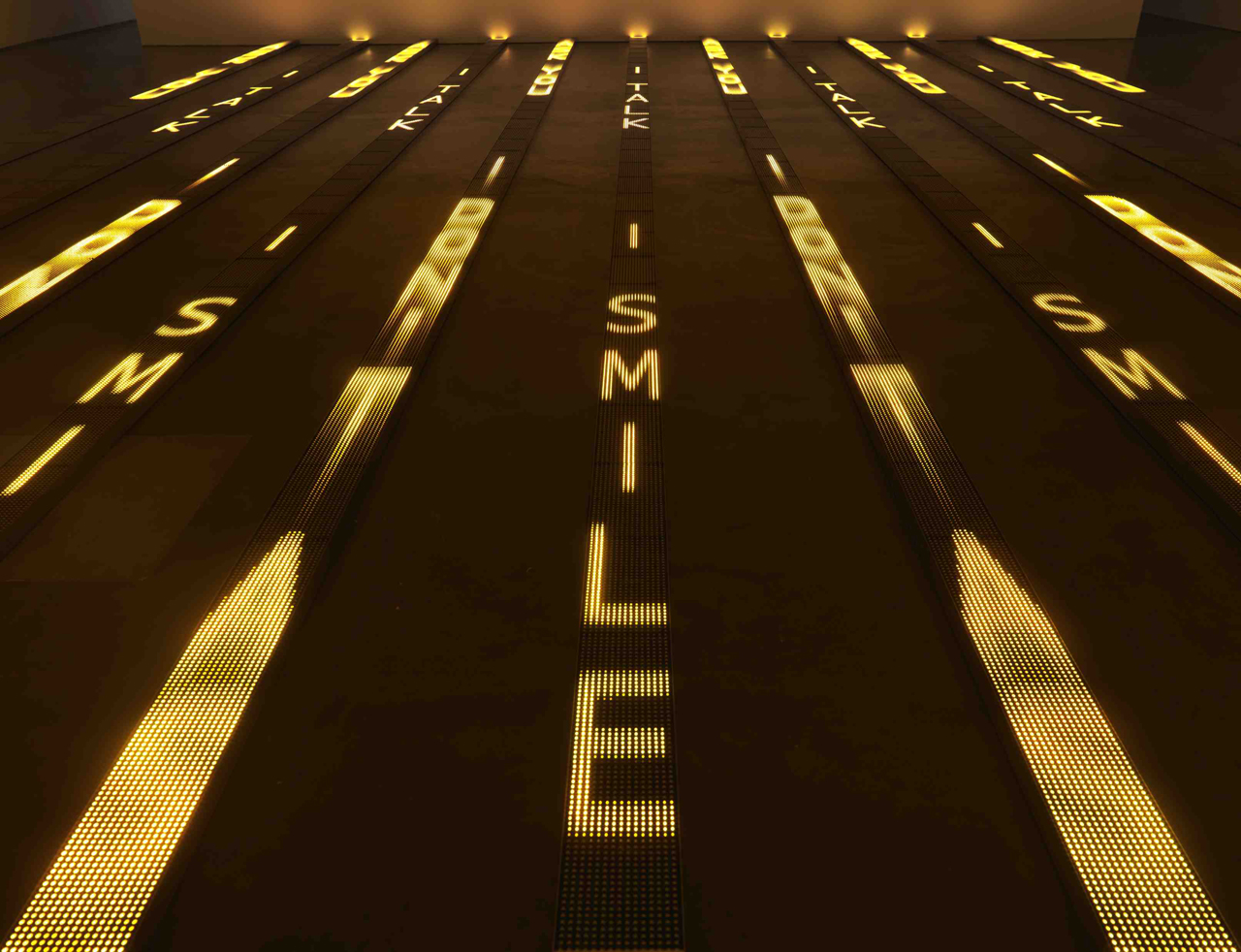

For more than thirty years, Jenny Holzer’s work has paired text and installation to examine personal and social realities