Foundation

Marc Quinn

October 5 → January 6, 2008

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

The PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art is currently exhibiting Two Planets Have Been Colliding for Thousands of Years (2017), a durational performance work by Spanish artist Dora García.

The work is simple, consisting of a white circle, with an off-centre hole, painted on the floor of a gallery space, and two performers, one in each circle. This duet, of sorts, has the two performers gazing languidly into each other’s eyes. Each performer changes position every so often to maintain comfort, a motion that engenders a responsive change of position from the other performer, all while maintaining a certain distance and the all-important eye contact.

The simplicity of Two Planets Have Been Colliding for Thousands of Years forms part of its strength; the work is stripped down to almost only this intimate exchange between the performers. Virtually no other stimulus—not even noise—is present, lending to the few stimuli that are there to be perceived, a subdued, emotionally resonant power. So unobstructed, the single perception of the performance takes on the full volume of the performers’ entire perceptive capacity. Rarely are we able to witness two people looking into each other’s eyes, let alone with the intensity that this kind of isolation of the phenomenon accords it. Walking in on a performance of Two Planets becomes a meditative experience for the viewer too, a period of oddly concentrated, contented gazing and intense, if subdued, emotional poignancy.

For its apparent simplicity, Two Planets operates a complex set of precariously practised performative relationships between performers and spectators, which balance self-consciousness, self-awareness, and the difficulty of forgetting oneself. The artist provides only the basic directive that the performers should always lock gazes and maintain a certain distance while staying in their assigned circles; allowing the game of positional adjustments be played out naturally by the performers. Freed from choreography and burdened with the responsibility of execute the performance through their own agency, the problem of performing Two Planets then becomes which gaze(s) performers are subject to, aware of, and influenced by; that is to say, for whom they perform, or to whom they perform.

In preparation for the presentation of her work, García stressed that as a performer, “you never perform for the public,” because the point of the work is to build an intimacy to which the gallery-goer may be privy. “When someone walks in [there should be] a feeling of intruding, that there is something going on there and they just happen to be in front of it. But it’s not for them.” [1]

The performers’ situation is a difficult one, because they must always “be very much aware that [they’re] not performing for [the audience, but] really performing for the other [performer]. This relation of intimacy and dependency that is created between the two [performers] is because [they] are performing for each other.” [2]

The performers in Two Planets are meant to attain a meditative focus while performing, to become completely absorbed in their exchange of gazes. However, the publicness of the performance—the potential presence of an audience looking upon their exchange—presents a significant impediment to realizing this meditative focus. How can one devote their entire focus to the intimacy of this exchange of gazes, when the vulnerability required by it is offered up to the audience’s “ubiquitous devouring eye”? [3]

The ability to forget the gaze of the Other—that radical alterity inscribed in the symbolic order, that generalized otherness which transcends identification with a single other subject [4] but is rather a generalized or societal otherness—and continue as if a screen were drawn between spectator and performer, is crucial to realizing the spirit of the work: that is, of performing only for each other, of giving over one’s complete focus, entire energy, and whole self to the act of gazing into the other’s eyes and reacting to their poses.

As subjects, Epstein explains, we are “ontologically dependent” [5] upon the gaze of the Other for our subjectification, meaning our self-fashioning and self-recognition. That is to say, we are dependent upon our relation to the Other—on the symbolization which the Other operates—both to make ourselves and to access our very being. “Yet this primordial relation to [the] self is mediated by the Other,” [6] so the presence of a gazing other inevitably has an effect on us. Sentenced as we are to intersubjective self-fashioning, to distance oneself from the gaze of the Other—the audience, in this case—is no easy task. To escape the automatic function of subjectification, which assimilates gazes, and screen oneself from the gaze of the Other; this is the key struggle in performing Two Planets.

Following Epstein, I would argue that every gaze—in how it reveals ourselves to ourselves and mediates our reflexivity—operates a signification of ourselves to ourselves, transmitted without an unassimilable remainder. Representation can never offer the fullness of experience and therefore always leaves behind an unassimilable remainder; it erases part of the signified from the idea it projects. This is an effect of systems of signification such as language: the signifier cannot contain the whole of the signified. Every symbol links us to a simplified idea of the thing it represents. And, in this way, being excessively available to the gaze of the Other means being constantly fed an ever-emptier signification and slowly losing some unassimilable remainder with every look. This disappearance of the object behind its signifier is part of Jacques Lacan’s conceptualization of aphanisis [7]; by extension, in being excessively signified through the gaze of the Other, we risk being aphanisized out of ourselves.

Thus, screening ourselves off from the gaze of the Other—from the “ubiquitous devouring eye,” the panopticon [8]—is essential to maintaining a self, and to prevent that self from being emptied out. No wonder a sideways glance is so easily noticed; it has the power to empty us out of ourselves.

What are performers to do in such a situation? How can one give one’s entire focus to the intimacy of exchanged gazes when the vulnerability required is offered up to the “ubiquitous devouring eye” of the audience? A physical screening-off is impossible, yet some form of gaze screening is necessary.

García’s answer is focus.

Two Planets takes place within two circles painted onto the floor of the gallery; one performer inhabits the inner circle, the second the outer circle. This becomes a stage upon which the work is presented, a zone that separates the audience from the performers, and which demands performance. García’s circles (fig. 2)—like Bruce Nauman’s marked perimeter of a square, [9] or the surface markings on roads—are examples of rehearsal frames, graphic structures which directs and constrains possibilities for action by organizing space and people so as to cultivate a certain rehearsal and re-rehearsal of forms. The circles activate the performers by creating a graphic structure or frame that positions them in a way that demands such a rehearsal.

The rehearsal frame for Two Planets is the linchpin of gaze screening for the performers. Like any other rehearsal frame, García’s circles both direct and constrain the performers’ agency; the circles create zones for them to inhabit, establish possible distances between them, demand of them a certain approach to posing through time, cordon them off from the audience, yet also leave them room to choose or change poses, among other things. The rehearsal frame permits us freedom only within limits, a readymade focus that deflects our attention from how it positions and directs us, instead, directing it toward what it allows us to do within the confines it has set.

García’s rehearsal frame sets in motion physical, but also symbolic strategies to assist the performers in gaze screening. The circles are painted onto the gallery floor in a white paint with visible brushstrokes. The particular paint used to produce the circles is Kool Ray Liquid Shade, normally used in agriculture to paint greenhouses, as an alternative to shade cloth, to shield plants from harsh sunlight and allow them ideal growing conditions. Kool Ray is a kind of film or screen drawn between the plants and the sun; as such, even the very materiality of the rehearsal frame is designed to screen off.

The circles establish a field akin to the sacred space of the mandala, a geometric spiritual tool understood to facilitate concentration and access to the spiritual through the power of the symbols organized within it. Indeed, the circles become a kind of mandala, which aids the performers in confining their focus and screens them off from the “ubiquitous devouring eye” of the audience. Stepping into the rehearsal frame is like putting on blinders, a means for directing our attention. The rehearsal frame upon/within which the performers move is itself a tool for shielding, a screen, a curtain drawn between performers and audience, a liquid shade that has been poured out for them. Indeed, the paint flakes and scrapes and marks clothing with the slightest touch; the performers constantly have chalky white traces on their clothes and skin. Like sunscreen, the liquid shade literally covers the performers. They stand upon a double signifier: the object of presentation is also a shield, which inaugurates a feedback loop of concentration that saturates the performers’ perceptual capacities, screening them off from (awareness of) the gaze of the Other.

[1] García, Dora. “Conversation with the Artist.” Recording of internal Meeting, July 2021, 1:08:10.

[2] García, Dora. “Conversation with the Artist.” Recording of internal Meeting, July 2021, 1:07:47.

[3] Epstein, Charlotte. “Surveillance, Privacy and the Making of the Modern Subject.” Body & Society, vol. 22, no. 2, 8 Feb. 2016, p. 33., doi:10.1177/1357034x15625339.

[4] “Other.” No Subject - An Encyclopedia of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, 15 June 2021, https://nosubject.com/Other.

[5] Epstein, Charlotte. “Surveillance, Privacy and the Making of the Modern Subject.” Body & Society, vol. 22, no. 2, 8 Feb. 2016, p. 35., doi:10.1177/1357034x15625339.

[6] Epstein, Charlotte. “Surveillance, Privacy and the Making of the Modern Subject.” Body & Society, vol. 22, no. 2, 8 Feb. 2016, p. 47., doi:10.1177/1357034x15625339. “Self-recognition is the mechanism underpinning reflexivity; hence the basis of autonomous agency.”

[7] Lacan, Jacques. “The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis”, Norton, 1998, p. 218.

[8] Sheridan, Alan, translator. Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, by Michel Foucault, Vintage Books, 1995, pp. 195–228.

[9] Nauman, Bruce. “Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square.” MoMA Learning, 1967, Museum of Modern Art, New-York, www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/bruce-nauman-walking-in-an-exaggerated-manner-around-the-perimeter-of-a-square-1967-68/.

This article was written as part of Platform. Platform is an initiative created and driven jointly by the PHI Foundation’s education, curatorial and Visitor Experience teams. Through varied research, creation and mediation activities in which they are invited to explore their own voices and interests, Platform fosters exchanges while acknowledging the Visitor Experience team members’ expertise.

Author: Paul Lofeodo

Paul Lofeodo was born in Toronto, Canada and now lives and works in Montréal where he received his Bachelor of Fine Arts with a minor in Sociology from Concordia University. Lofeodo makes photo-based installations dealing with themes of embodiment, performance, hegemony, violence and indexical relations. Influenced by his studies in Sociology, Lofeodo applies marxist and psychoanalytic perspectives to the embodied practices of tradition, identity and social institutions.

Foundation

Gathering over forty recent works, DHC/ART’s inaugural exhibition by conceptual artist Marc Quinn is the largest ever mounted in North America and the artist’s first solo show in Canada

Foundation

Six artists present works that in some way critically re-stage films, media spectacles, popular culture and, in one case, private moments of daily life

Foundation

This poetic and often touching project speaks to us all about our relation to the loved one

Foundation

DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art is pleased to present the North American premiere of Christian Marclay’s Replay, a major exhibition gathering works in video by the internationally acclaimed artist

Foundation

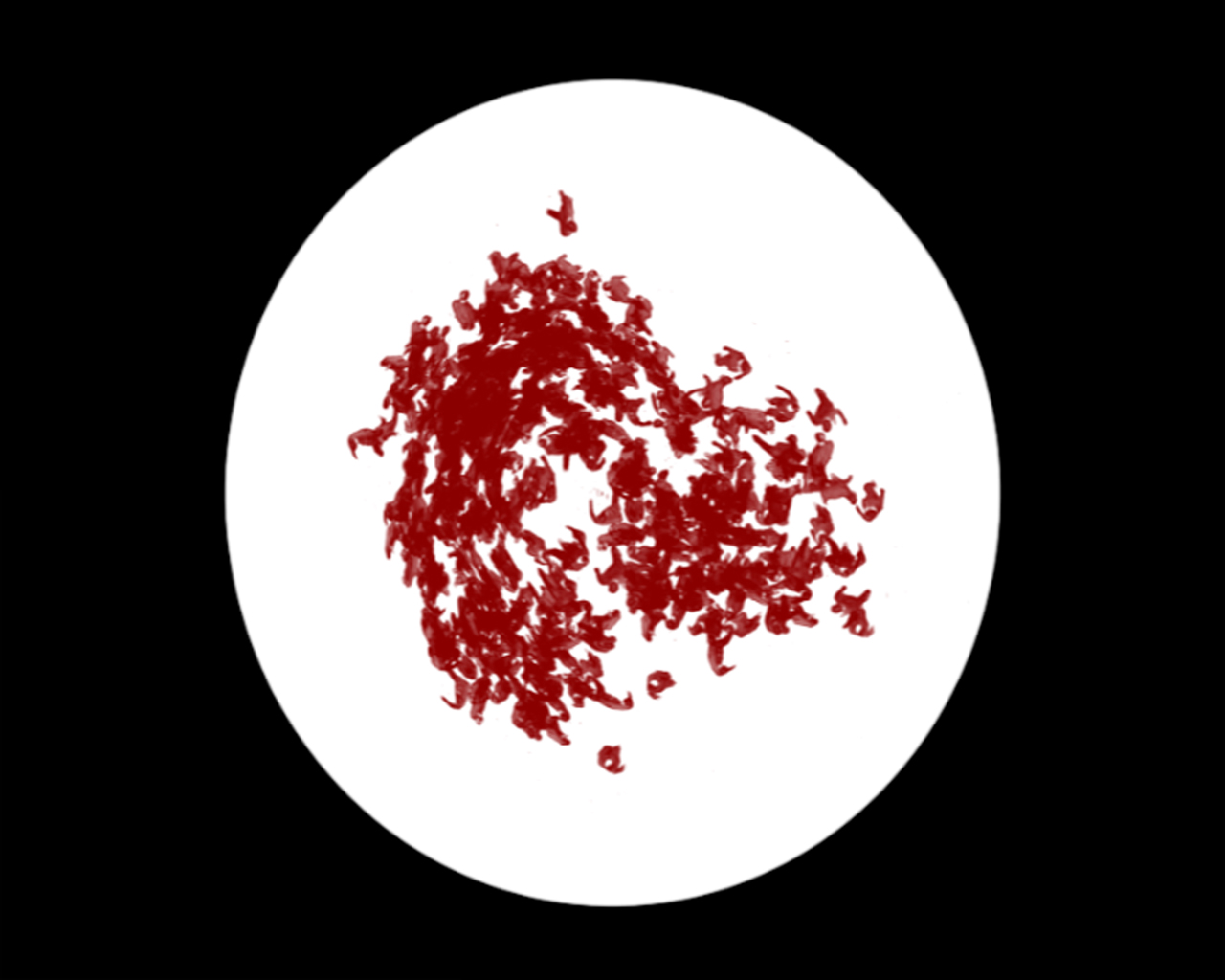

DHC/ART is pleased to present Particles of Reality, the first solo exhibition in Canada of the celebrated Israeli artist Michal Rovner, who divides her time between New York City and a farm in Israel

Foundation

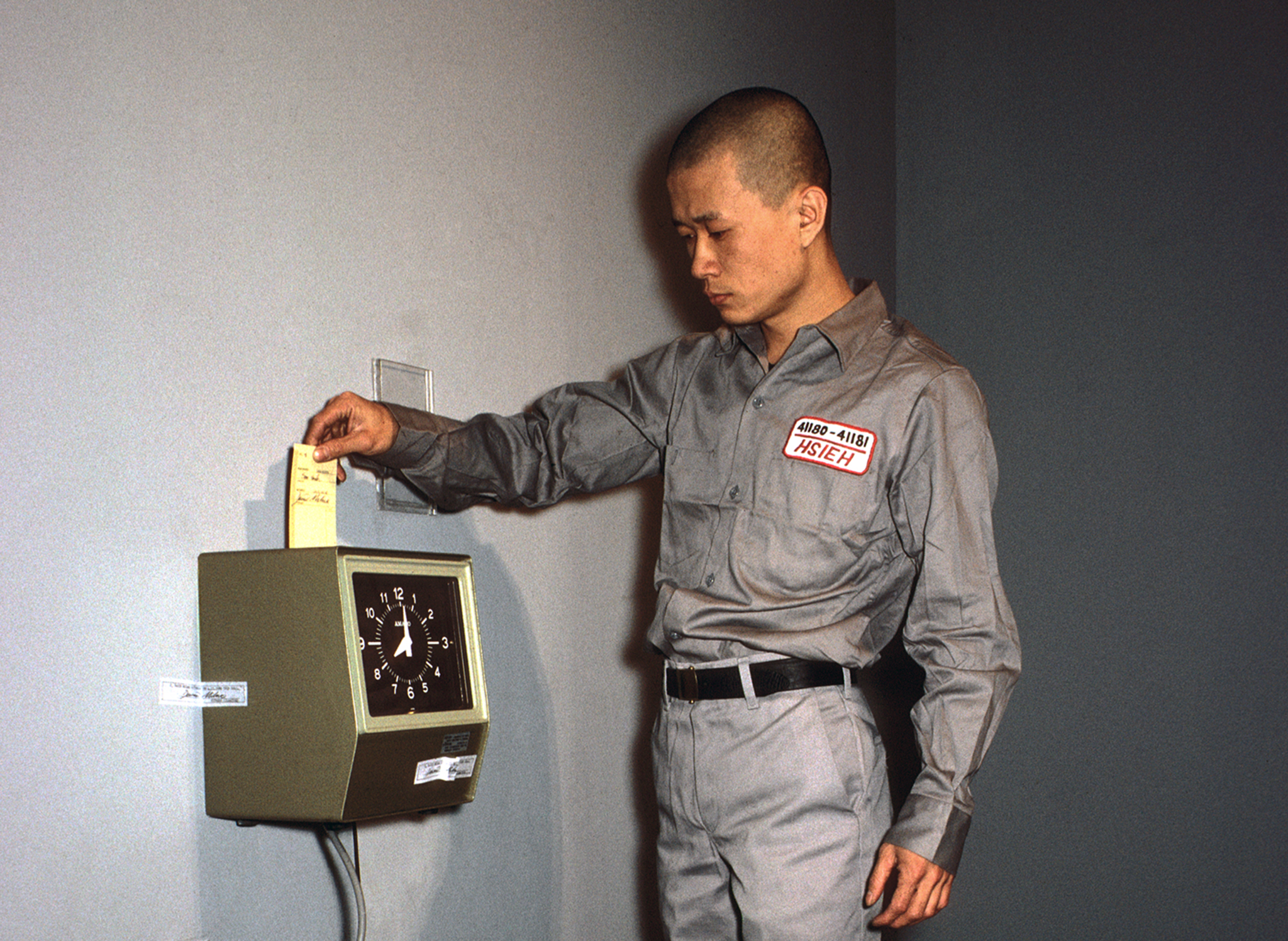

The inaugural DHC Session exhibition, Living Time, brings together selected documentation of renowned Taiwanese-American performance artist Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances and the films of young Dutch artist, Guido van der Werve

Foundation

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film installations experiment with narrative storytelling, creating extraordinary tales out of ordinary human experiences

Foundation

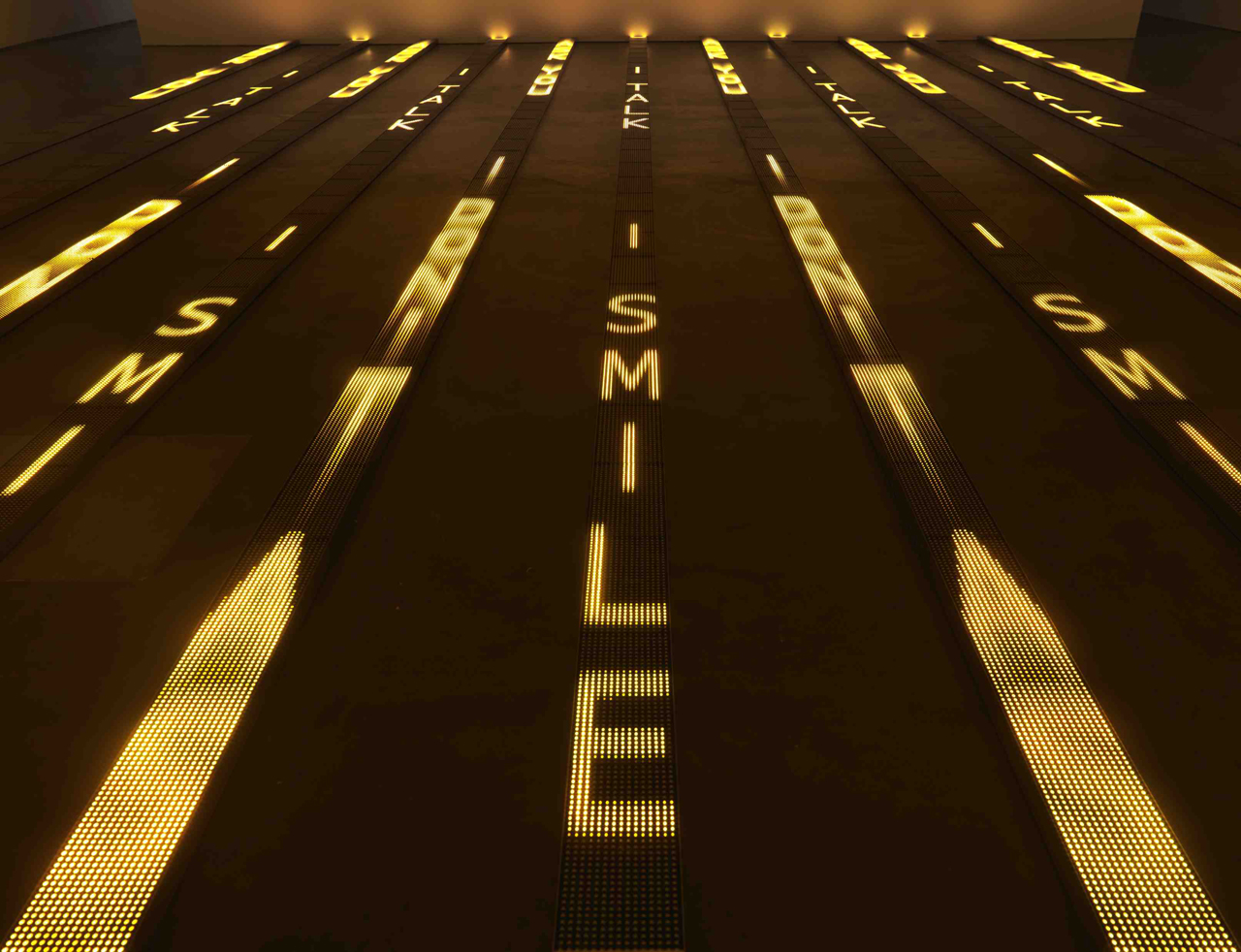

For more than thirty years, Jenny Holzer’s work has paired text and installation to examine personal and social realities